Challenging Faith Based Hate: True Stories

16 / 02 / 24

Menu

01 / 07 / 20

Phil Champain, Director of the Faith & Belief Forum

Race and faith. Two short words. Two descriptors of identity. Both distinct, and interconnected. At the Faith & Belief Forum (F&BF) we have been working on this interconnectedness for some time. For example, we established a Race & Faith Working Group a year ago; race and faith are key aspects of our ongoing work on Equality Diversity and Inclusion (EDI); and we are in the process of becoming a signatory to the Race at Work Charter.

There are other dimensions to our identities of course, beyond race and faith, including gender, age, LGBT+, and class. We need to engage with all of them – to be able to express our whole selves. This is our business at F&BF. Race and LGBT+ are current priorities.

As a middle class, white, middle aged, atheist, straight, male I am in that category where thinking about these different but interconnected aspects of my own identity has always been and continues to be critical. It is critical because none of my identity characteristics carry the accompanying labels of ‘minority’ or ‘oppressed.’ Rather, they are more commonly associated with dominance and oppression – men over women, old over young, straight over gay, white over black. Working to change this picture is paramount for me.

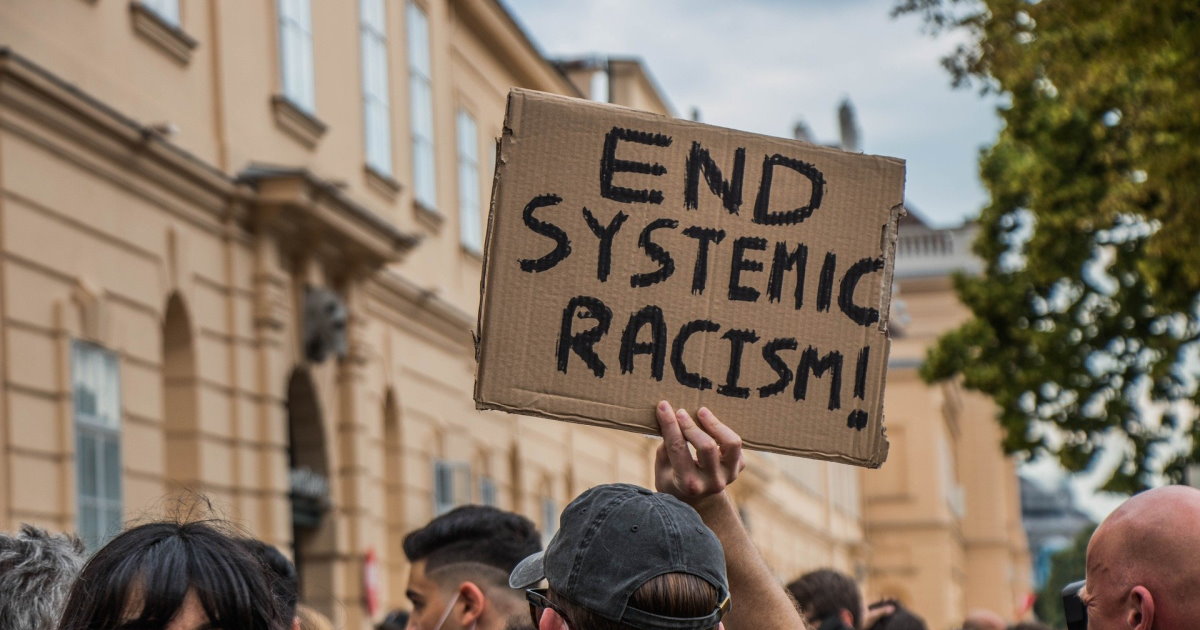

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement began seven years ago in 2013 after George Zimmerman’s acquittal for the killing of Trayvon Martin in Florida. The recent tragic and horrendous killing of George Floyd has sparked renewed protest. It should not take another racist murder of a black man to be the catalyst for this and other blogs. But write I must, for reasons that go to the heart of the institutionalised nature of anti-black racism and other isms in our society, and the implications for our interfaith work.

To be credible in our response to current demands for change, those of us working to improve community relations in the UK (and elsewhere) need to be engaging institutions as well as individuals. Of course, both are linked. But addressing institutional change requires specific strategies and perspectives that may be different to those we are used to. We need to focus on the institution, not only on the individual. We should remember in doing so that ‘institutions’ are not necessarily the same as organisations. They are also the customs, rules and norms that, over time, have become accepted by our society or community. Unfortunately, these norms currently include the lack of active challenge to and dismantling of anti-black racism.

The roots of this problem with our institutions go a long way back and, as the victims will remind us, resist quick fixes. The Belgian economist Gerard Roland has an interesting take on different types of institutions, distinguishing those that are fast moving from slow moving. While he suggests that political institutions can move rapidly and in large steps (as evidenced perhaps by the recent radical measures taken to provide financial support during the covid-19 crisis), ‘individual social norms…tend to change rather slowly.’

Arguably the most racist political policy of any era was the one that allowed white people to call black people property. This practice was known as ‘chattel slavery’, whereby an enslaved person was owned for ever, and their children and children’s children automatically enslaved. The origins of this practice can be traced back to 1619. However, as recently as two years ago, the UK Treasury was forced to delete a tweet that declared wrongly that ‘millions of you helped end the slave trade through your taxes’. Although the slave trade was abolished in 1807 and slavery itself in the UK by the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act, it was the slave owners rather than the enslaved who received the millions in compensation through our taxes. Political policy can move fast. Changing the social attitudes that become entrenched through such policies is slow, painful, and fatal in the case of activists such as Martin Luther King.

Anti-black and other forms of racism have become so ingrained in our society that tweeters in the Treasury and other institutions continue to fall short in facing up to the fact that they remain more part of the problem than the solution. The Prime Minister has launched a commission to look at racial inequality (another one I hear you say) and the Equality and Human Rights Commission is launching an enquiry into ‘long standing race inequality‘ which has been thrown into stark relief by the coronavirus pandemic. But questions remain – how can we speed up the pace of institutional change? What must the interfaith sector do in this regard? Here are three suggestions, none of them novel, but nevertheless worthy of restating.

First, we need to get our own house in order. Those of us leading and shaping interfaith institutions need to make sure that we are inclusive of minorities and in the case of the BLM movement, of black voices. We must make sure those we recruit to deliver our programmes include these voices and understand them; we must get better at engaging with black people of faith; and be vigilant of the diversity of perspectives amongst those we apply this label to.

Second, we must raise the bar in terms of what we are aspiring to change. It is not enough to focus only on the individual. We must commit to changing institutions. Yes, our work is always about engaging with individuals. But our higher goals and outcomes must be about institutional change though our engagement with individuals in these institutions. We must aim to change systems and structures, dismantling old racist ones and building new, inclusive, and respectful ones.

How to do this brings me to my third and final point. We need to address head on the link between political institutions and social norms. This means more dialogue between political institutions and minorities; more dialogue between minority faith groups and local government; more capacity to engage with minority faith groups within government (including greater representation of black and minority voices within central and local government); and more capacity within black and other minority faith communities to engage with political institutions.

At F&BF we have much to do on all three fronts. Yes, we have made progress. Our ParliaMentors programme is connecting young people from minority faiths with political institutions; our community dialogue work is building relationships between minority faith groups and local government; and we are changing our recruitment policies to increase our chances of recruiting people from black and other minority communities. However, there is a long way to go. We might agree with Gerard Roland that social norms change slowly. But this may be another ‘norm’ we need to challenge. We must move faster! Only then can we say with confidence that we are more part of the solution than the problem.

16 / 02 / 24

15 / 02 / 24

16 / 01 / 24