Challenging Faith Based Hate: True Stories

16 / 02 / 24

Menu

01 / 06 / 21

by Gina Dadaglo

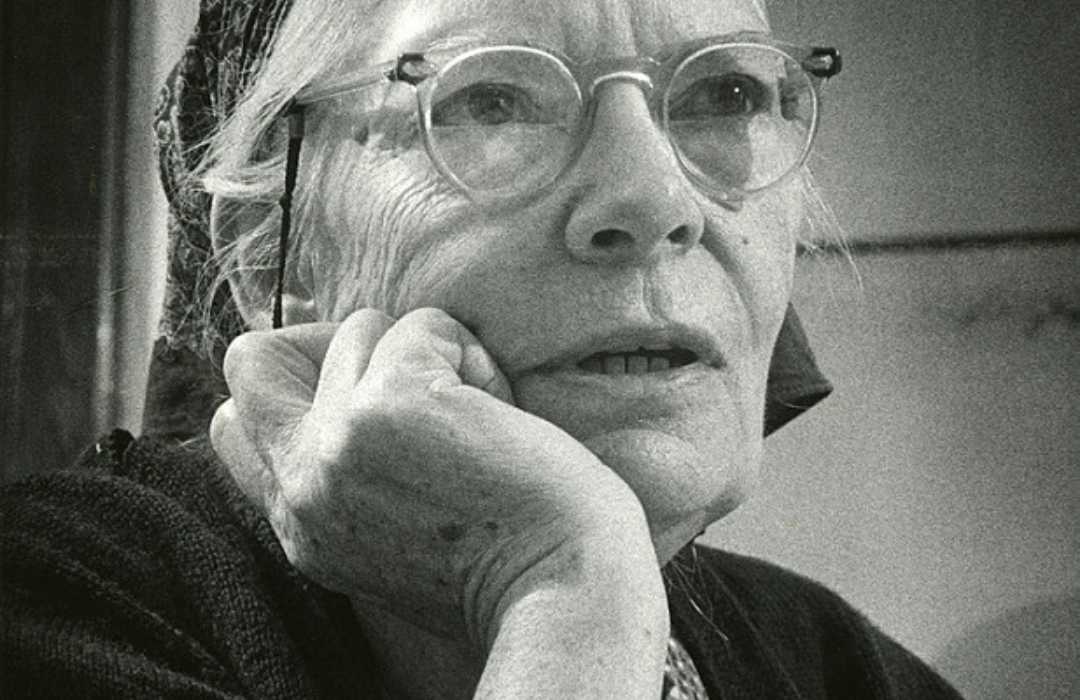

Dorothy Day (1897-1980) was a Catholic convert and an activist who did not fit into any neat boxes. Even her legacy is controversial: many Catholics are suspicious of her sympathies with Communism and her readiness to engage in civil disobedience, whilst left-wing activists are outraged by her orthodox Catholic faith and wilful submission to Church hierarchy and tradition. She did not care whether she received praise or approval, but nor did she seek to be subversive. She simply lived according to what she believed to be right and true, without expecting thanks or admiration. In fact, she famously quipped “Don’t call me a saint” – but she is, in fact, on the path to canonization.

To describe Dorothy Day as “inspirational” feels a little trite, and perhaps not even accurate. I think of her as someone to anchor my hope upon. This is in part because of her life story, and in part because of her attitude. Before becoming Catholic, Dorothy went through divorce, an abortion, and had a child out of wedlock – each instance involving a different man. After conversion, she did not seek to hide or dismiss these parts of her life, although she deeply regretted the abortion in particular. Rather, they fuelled her compassion for the pain of others, and she understood that her faith did not give her the right to judge the actions of others; it gave her a mandate to love and serve them.

Dorothy Day is most famous for having founded the Catholic Worker Movement and publishing the Catholic Worker newspaper (which is still published today). She and co-founder Peter Maurin had a vision for social justice which they believed was ultimately realised within the life of Christ and the social teachings of the Catholic Church. The Movement was founded in response to the needs of the Great Depression and consisted primarily of the creation of houses of hospitality in low-income areas around the United States. These houses were run by volunteers who provided food, clothing, shelter, and most importantly, fraternity, to those who were suffering. There are 134 Catholic Worker houses still in existence today.

Whilst this work is, in itself, admirable, what is even more impressive is that Day did not believe she was owed thanks for it. In fact, the people who made use of the services were often quite ungrateful, rude, even aggressive, but to Day this was irrelevant. Furthermore, she had little time for those who claimed to love and care for the poor in word but not in deed. The verse “let us not love in word or talk but in deed and in truth” (1 John 3:18) summarises the philosophy of the Catholic Worker Movement: if you wanted to support their work, you should expect to roll your sleeves up and be ready to do the hard labour involved in living a life of service. To simply vocalise support for the Movement or to throw money at it was to entirely misunderstand what it was about: living and sharing in community with the poor.

Although her work was grounded in tangible, material provision, the spiritual dimension was indispensable. Those who visited Catholic Worker houses were invited to pray with the staff, and although this was entirely optional, Dorothy said that anyone who visited without participating in the rhythms of prayer were “missing the whole point.” Prayer and relationship with God was the lifeblood of the Movement and whilst this may have been invisible or even absurd to onlookers, for Dorothy it was as fundamental as having bread to offer. She was doggedly committed to a life of prayer, and saw it as a duty much like her practical labours. Although she may not “feel like” praying all the time, it was an essential act of service to God and neighbour, and she therefore afforded herself no excuses when it came to devoting hours of her day to prayer and communion with God.

However, despite Day’s commitment to the Church, she was not uncritical of the people who comprise it. She rejected any politicisation of the faith, for example refusing to get behind the Church’s alliance with Franco during the Spanish Civil War, but equally rejecting the atheistic and anticlerical Republican forces. During the Vietnam War, she went to Rome to petition the Pope to do away with the notion of a “just war”, and lobbied for the Church to adopt nonviolence as a tenet of the faith. Many “hippies” admired her work, but she was critical of hippie culture, seeing it as a self-indulgent middle-class movement devoid of any real commitment to the poor. Her own life was one of voluntary poverty, which she believed was critical in order to live in true solidarity with the oppressed, and she took the Biblical command to “generously share what you have with those who ask for help” (Matthew 5:42) completely literally. She did not claim any possessions as her own, and was always ready to give away her clothes, food, and any other belongings to those whose needs were greater.

My life looks nothing like Dorothy’s, but I still look to her example in my role as a wife and mother. Even if I don’t feel like cooking, this is how I can serve those who need me. When a child interrupts me while I fold laundry or read a book, I try to remind myself that my time is a gift and a resource that I can share with those in my care. When I don’t feel like praying, I try to recall Dorothy’s attitude, and think of it as an indispensable part of my day. Of course, I fail regularly to do this with the grace and grit that she did, but when I think of Dorothy, I am reminded to look beyond my own wants and needs to those of the people around me.

16 / 02 / 24

15 / 02 / 24

16 / 01 / 24