Challenging Faith Based Hate: True Stories

16 / 02 / 24

Menu

17 / 12 / 20

By Jennifer Uzzell

Midwinter is a time for feasting, merriment and light for people of many different religious traditions around the world, and Pagans are no different. Like many others we will be lighting candles to welcome the birth of light and hope anew into the world. Under more usual circumstances we would be meeting family and friends and taking part in ceremonies to celebrate the festive season, but of course that is not possible and so for most of us this Midwinter will be a combination of solitary or family ceremonies and online gatherings.

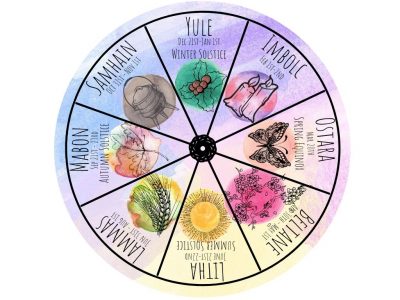

But who are the Pagans? ‘Pagan’ is not a religion so much as an umbrella term for a number of religious or spiritual traditions that are different, but which share certain ‘family traits’, such as a tendency to see and revere the divine in the natural world. In the UK, the most common Pagan traditions are Wiccans and Witches, Druids, Heathens, and people who identify as Pagan but do not follow a particular path, these are sometimes called Eclectic Pagans. There are also people who follow the ancient pantheons of other civilisations such as Egypt, Greece or Samaria. All of these traditions have different deities, festivals and rituals but many of them follow the Wheel of the Year.

This is a set of eight seasonal festivals which have their roots in the ancient past of Britain. The Wheel of the Year was introduced in its present form in the middle of the Twentieth Century by Ross Nichols and Gerald Gardner, foundational figures in Wicca and Druidry respectively. One of the most important festivals on the Wheel occurs on or around the Winter Solstice (between 20th and 21st December) when the sun appears to stand still at its lowest point and the night is the longest. This is the ‘midnight of the year’, the time of greatest darkness and cold. Many Pagans, particularly Heathens, who follow the gods of the Northern tradition (Anglo Saxon or ‘Viking’) know this festival as ‘Yule’, although this name has also been adopted by many other Pagans. For many Druids it is ‘Alban Arthur’ The light of Arthur, or Artus the Bear- associated with the North and the night sky. For many other Pagans it is simply the Winter Solstice.

In the Ancient Roman cult of Mithras, 25th December was the birthday of Sol Invictus- the Unconquered Sun, one of the titles of the semi divine Mithras; and Pagans still celebrate this time as a time of birth. There are many myths that tell of a birth at this time. Druids might associate Midwinter with the birth of the Mabon, a divine child that represents light and hope, as well as the return of the sun. There are several altars from Roman Britain to ‘Maponus’ the Divine Youth, whom the Romans may have associated with Mercury. In Medieval Welsh stories, which some Pagans believe hold traces of pre-Christian religion, Mabon is a mysterious child who is abducted from his mother and for whom a great search, led by Arthur, is held. This is not explicitly associated in the Welsh story (which can be found in the ‘Mabinogi’) with either the sun or the midwinter, but the association suggests itself and in a way that is all that matters.

To Pagans, stories are the very lifeblood of what it means to be human; in a very real way, we are the stories that we tell about ourselves. At Midwinter, the story of the birth, or the finding of a divine child who represents the return of the light of the sun and hope for the coming year is one that has universal appeal. The return of the sun at the Midwinter Solstice is not always linked to the birth of a child, but it is always celebrated with rituals to welcome it and rejoice in its renewed light and heat and the new fertility that it brings to the land.

Many Pagans celebrate the Solstice in ways that their Christian neighbours would find entirely familiar. In fact, some take great delight in attending Midnight Mass or carol services in Church. This becomes less surprising when you realise that Pagans, like Christians, are celebrating the birth of light and hope, sometimes in the form of a divine child. Candles are likely to form a central part of any Solstice ceremony. Often all lights are extinguished, to be relit from a single candle. In Druid ritual, this candle is carried by the youngest person present, in the role of the Mabon. The central idea is to celebrate the return of the light out of the darkness.

Mistletoe also features in many Pagan rituals at this time. It has a special ‘liminal’ quality as it is ‘born between heaven and earth’ growing parasitically on trees, particularly oak and apple, both of which have particular significance for Druids. It is cut with great ceremony and brought into ceremonial spaces and houses as a blessing for the new year. Traditionally last year’s mistletoe is ritually burnt at this time. For Heathens, the mistletoe is associated with the death of the god Baldur and his descent to the Underworld. For Druids, the plant has had sacred associations since the Iron Age, if Pliny is to be believed. He records a Druidic mistletoe cutting ceremony where the plant is cut from an oak using a golden sickle, which may have represented the moon. The ceremony also involved the sacrifice of two white oxen, but thankfully things have moved on since then.

Many Pagan midwinter ceremonies involve a ritual fight between the Oak King of the summer and the Holly King of the winter. Contrary to what you might expect, at the Winter Solstice the Holly King is defeated by the Oak King as the sun begins to regain his powers, building to his greatest strength at the Summer Solstice, when he is defeated by the Holly King and the world begins its journey into darkness once more. Another tradition, which dates from at least the Middle Ages is the Yule log, which is brought into the house and decorated, before being burnt in the hearth to ensure a prosperous new year. For those who don’t have a real fire, this may be decorated with candles instead.

There is always much controversy at this time of year about the origins of many Christmas customs such as Christmas trees, Yule logs and Father Christmas or Santa Claus. Are they Christian or Pagan? Who ‘stole’ them from whom? In the end it really doesn’t matter. Pagan and Christian traditions have existed alongside each other in the British Isles for at least 1500 years and they have grown into each other. Ideas have continually passed backwards and forward between them and continue to do so. This Christmas I will be joyfully raising a glass with my Christian friends and neighbours (virtually, of course) to toast the return of light, warmth and hope into the world.

A very blessed Yule to you all!

About the author:

Jenny Uzzell is the Education and Youth Manager for the Pagan Federation. She is a Druid, being a member of OBOD at Ovate Grade, BDO at Bardic Grade, and TDN. She has represented the Pagan Federation on the Religious Education Council for 7 years and has also been involved with the REC’s Task 2 Committee looking into the role of Examining in RE. Jenny is currently a PhD student at Durham University working under the auspices of the Centre for Death and Life Studies, and is the a co-owner and director of a funeral home.

16 / 02 / 24

15 / 02 / 24

16 / 01 / 24